Understanding and Sustaining Family Business Success

In this issue of The Family Business Bulletin, we examine what makes family-owned enterprises unique – from their structure and global trends to their performance – highlighting the story of the Taylor Companies, a Mississippi-rooted business thriving across generations and borders.

INFORMATION – Definition

What is a Family Firm, and Who Can Be Part of It?

by Dr. Laura Marler

What is a family firm? This is a seemingly simple question with a somewhat complex answer. Family firms, the predominant form of business around the world, take all shapes and sizes. Many of us think of them as small, local businesses, which is often the case. However, Walmart, Ford Motor Company, and Dell Technologies are family firms as well. Thus, these businesses are not defined by their size but rather by their ownership and goals. While the definition of a family firm has been debated, commonalities that cross most definitions are the presence of family ownership and a desire for the family to maintain control for generations to come (Chua et al., 1999).

Family firms are characterized by long-term orientation and higher levels of risk aversion than their non-family counterparts. These characteristics emerge from their desire to preserve the firms for future generations. They often have community-like cultures with a paternalistic management style toward all employees – both family and non-family. As a result of these characteristics, they are less likely to lay off employees, even during economic downturns. Thus, they are noted for their economic stability around the world.

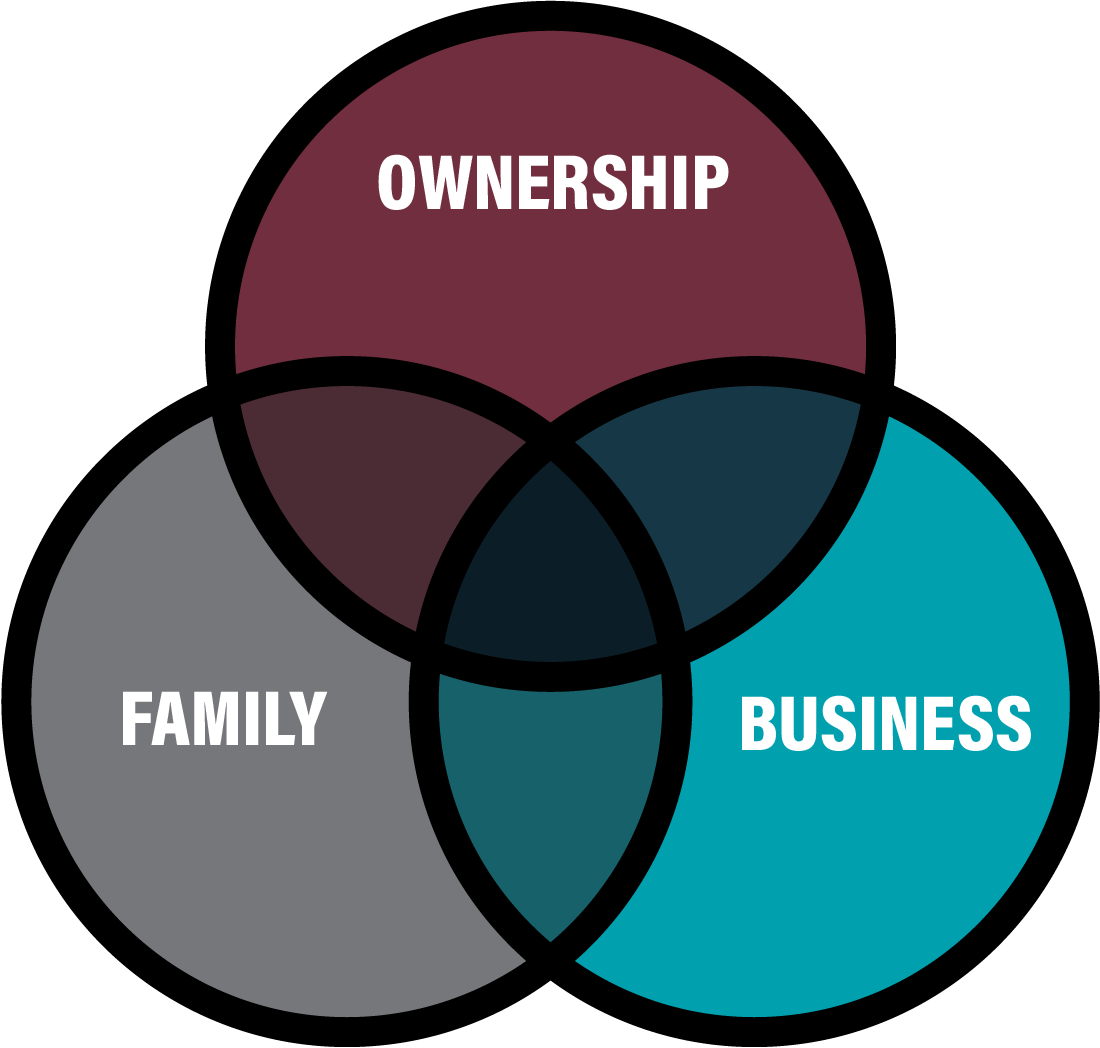

The unique synergy and complexity of family firms often lie within the overlap and interdependent nature of three systems: family, business, and ownership. The three-circle model developed by Tagiuri and Davis (1996) is a useful illustration of the complexity that results from overlapping systems consisting of seven groups:

- Non-family owners not involved in the business as managers or employees

- Non-family owners involved in the business as managers or employees

- Non-family managers or employees who are not owners

- Family managers or employees who are not owners

- Family members not involved in the business as owners, managers, or employees. This may include descendants or spouses/partners of owners.

- Family owners not involved in the business as managers or employees

- Family owners involved in the business as managers or employees

A family owner is often a founder of the business. Individuals who compose the family system often serve as a source of slack resources in the early stages of a firm’s development and frequently represent the main labor source. However, non-family managers and employees in the business system often enable a firm to grow over time and can add technical expertise not possessed by family members. The functionality of each of the three systems has an impact on the family business as a whole. Given the interdependent nature of the three systems, conflict in any one is likely to spill over to the other parts. For instance, conflict between family members can lead to contention in the firm if other family and non-family members are forced to choose sides. In addition, family employees may embody differing norms and expectations than non-family employees, which can lead to an “us versus them” mentality. Non-family employees may feel as though they are second-class citizens who lack the pathways to advancement offered to family employees who have grown up in the firm. Tensions can also emerge when family owners who are not employees seek to influence firm decisions.

All this to say, at the heart of family firms lies complexity. Those that successfully navigate this complexity are more likely to achieve superior performance; firms that do not are almost all doomed to failure. Therefore, a recipe for success involves ingredients such as strong family values, sound business practices, and informed and enlightened owners.

Chua, J.H., Chrisman, J.J., & Sharma, P. (1999). Defining the family business by behavior. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 23 (4), 19-39.

Tagiuri, R. & Davis, J. (1996). Bivalent attributes of the family firm. Family Business Review, 9 (2), 199-208.

DATA – The World

How Prevalent are Family Firms Around the World?

by Dr. Jim Chrisman; Myles Melancon (Management PhD student); Tyler Burch (Management PhD student)

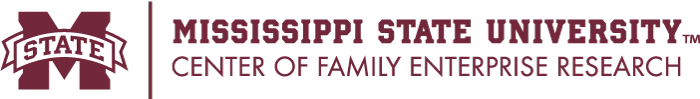

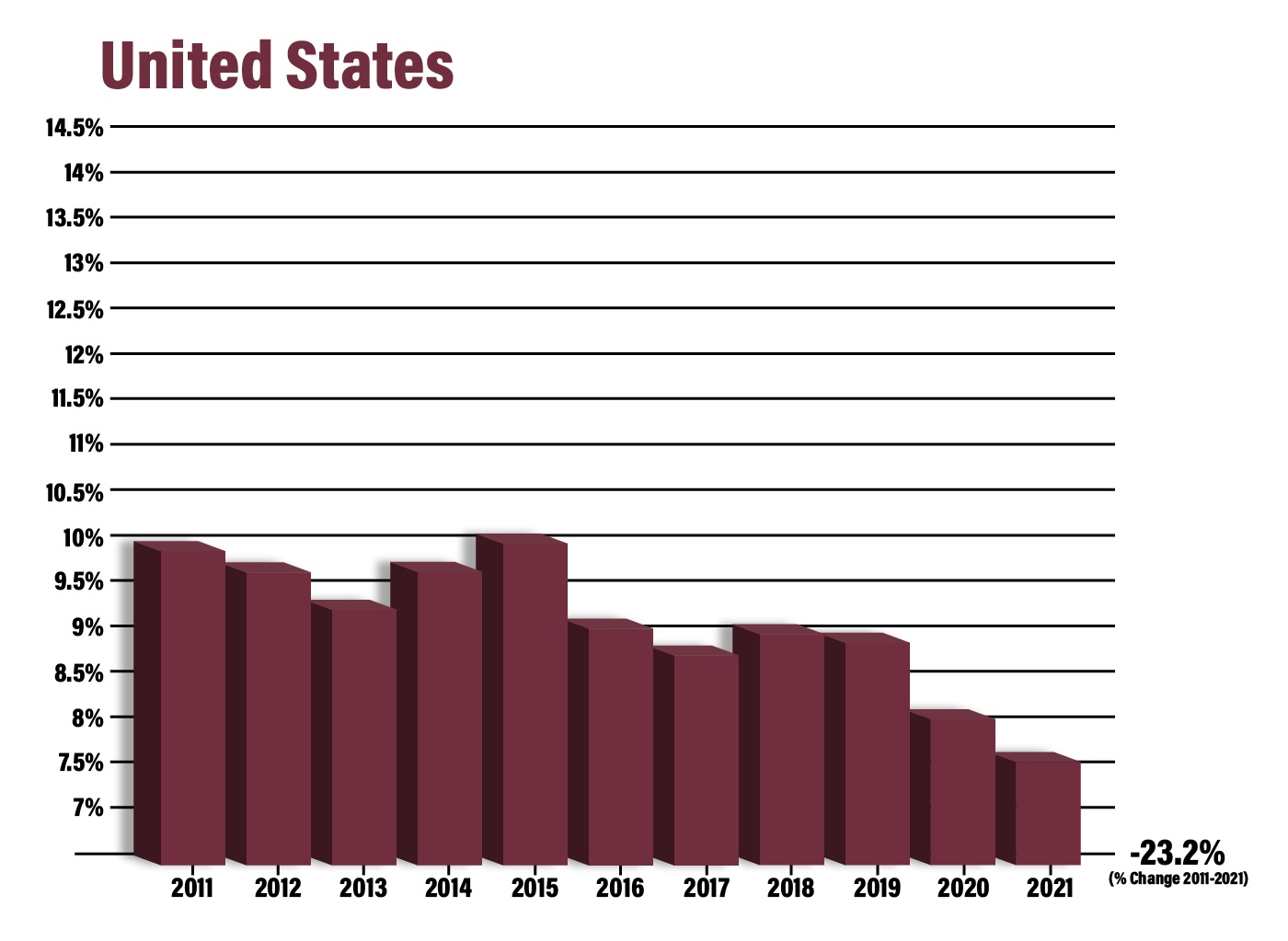

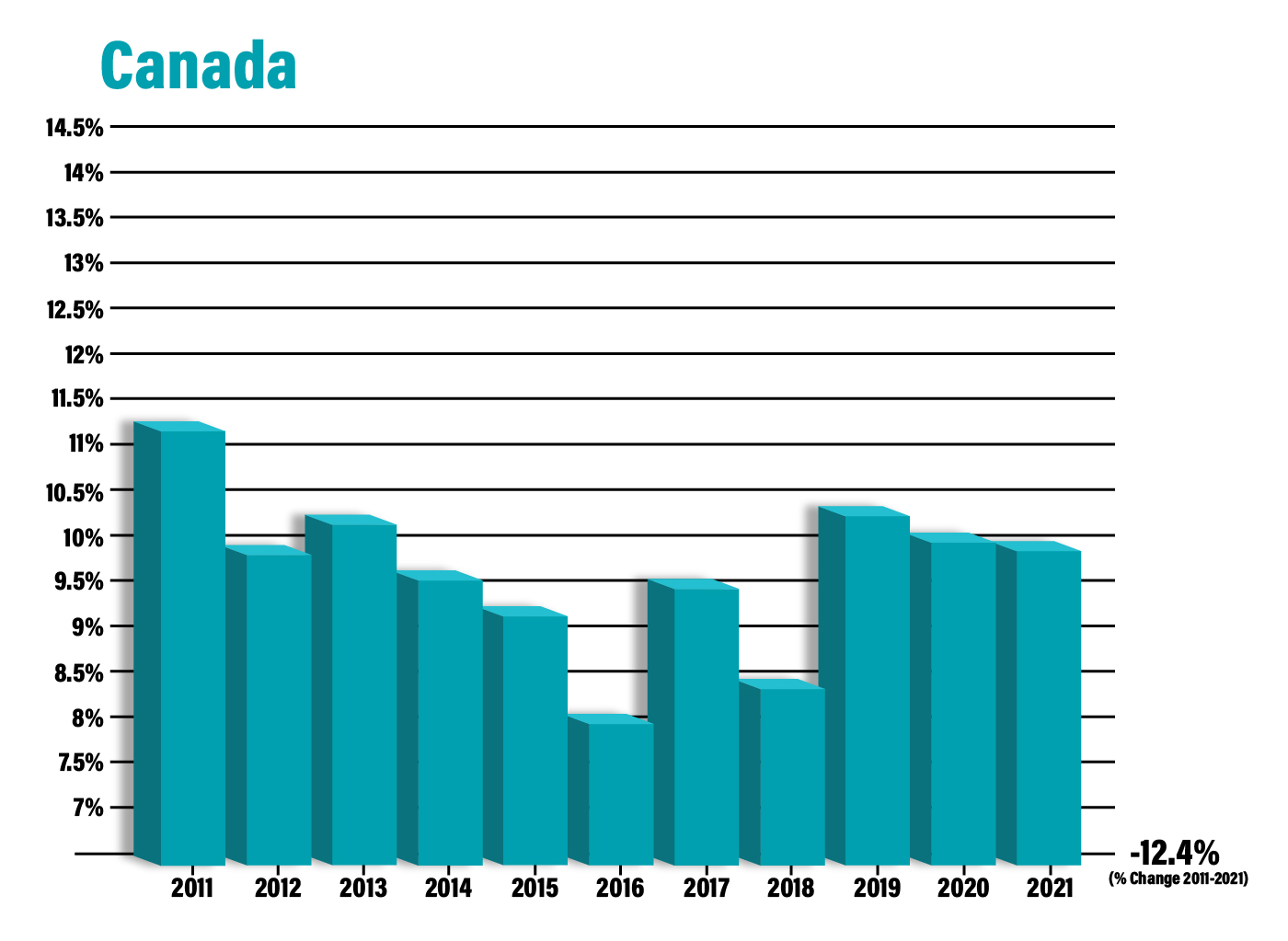

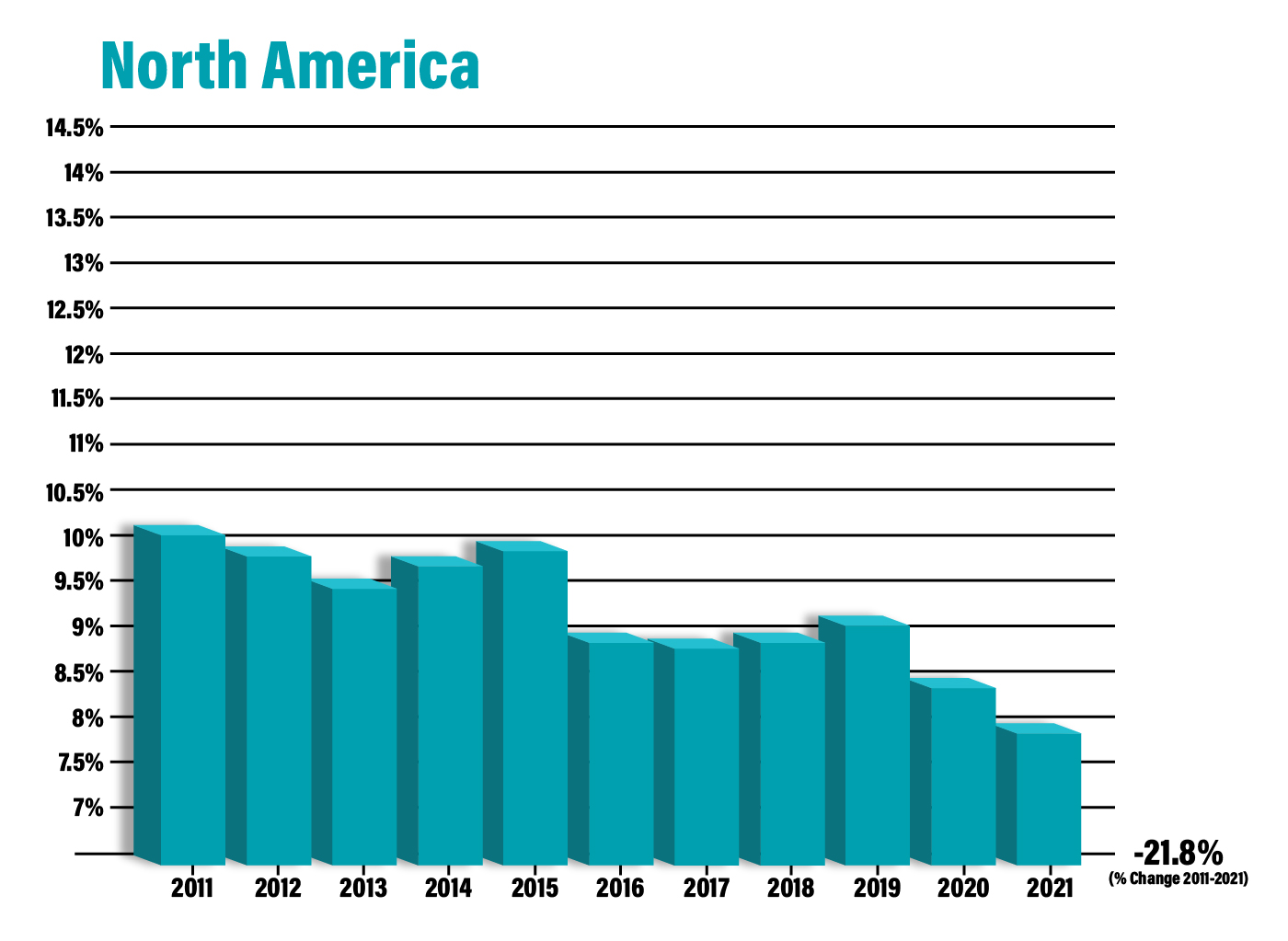

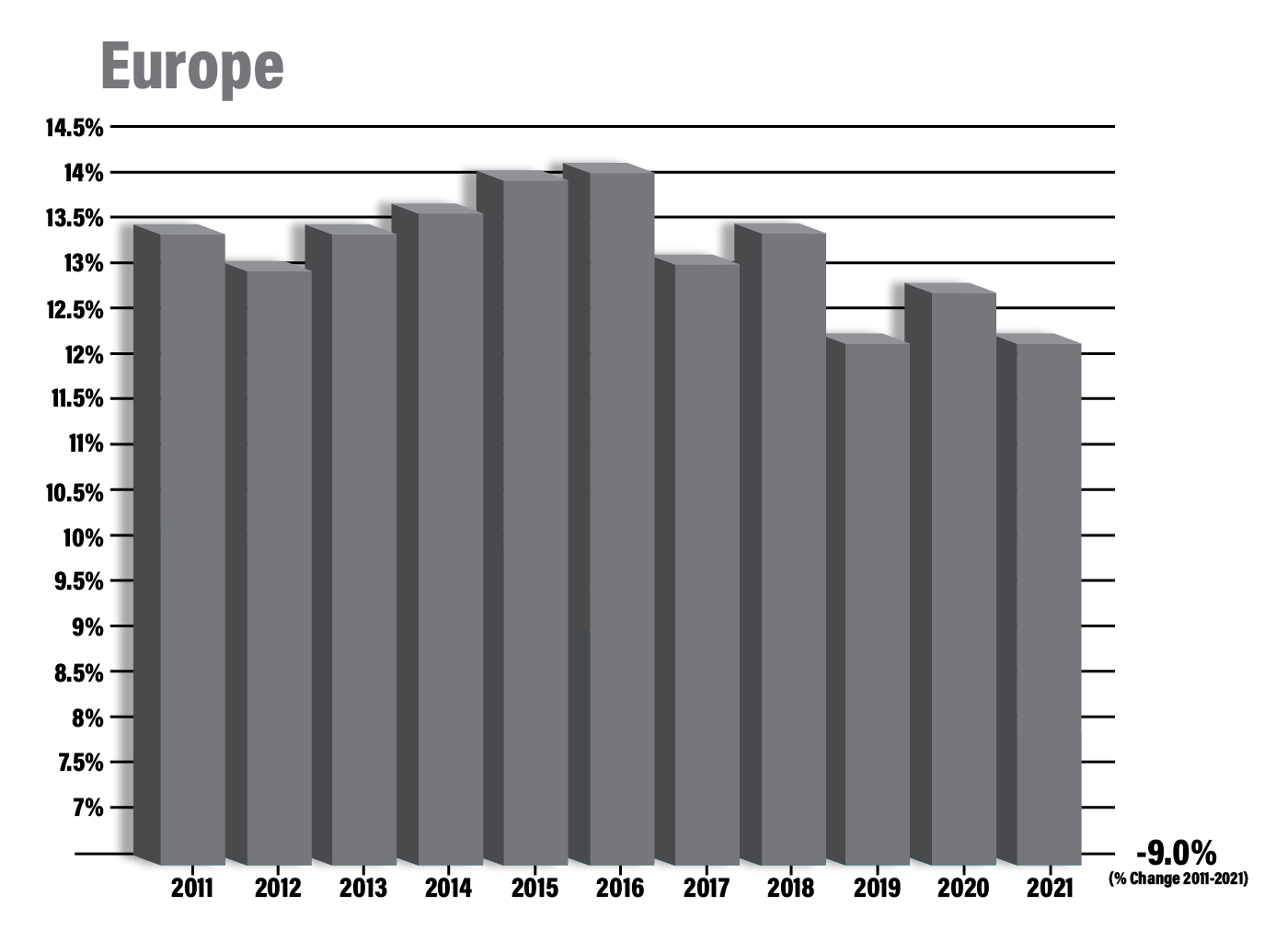

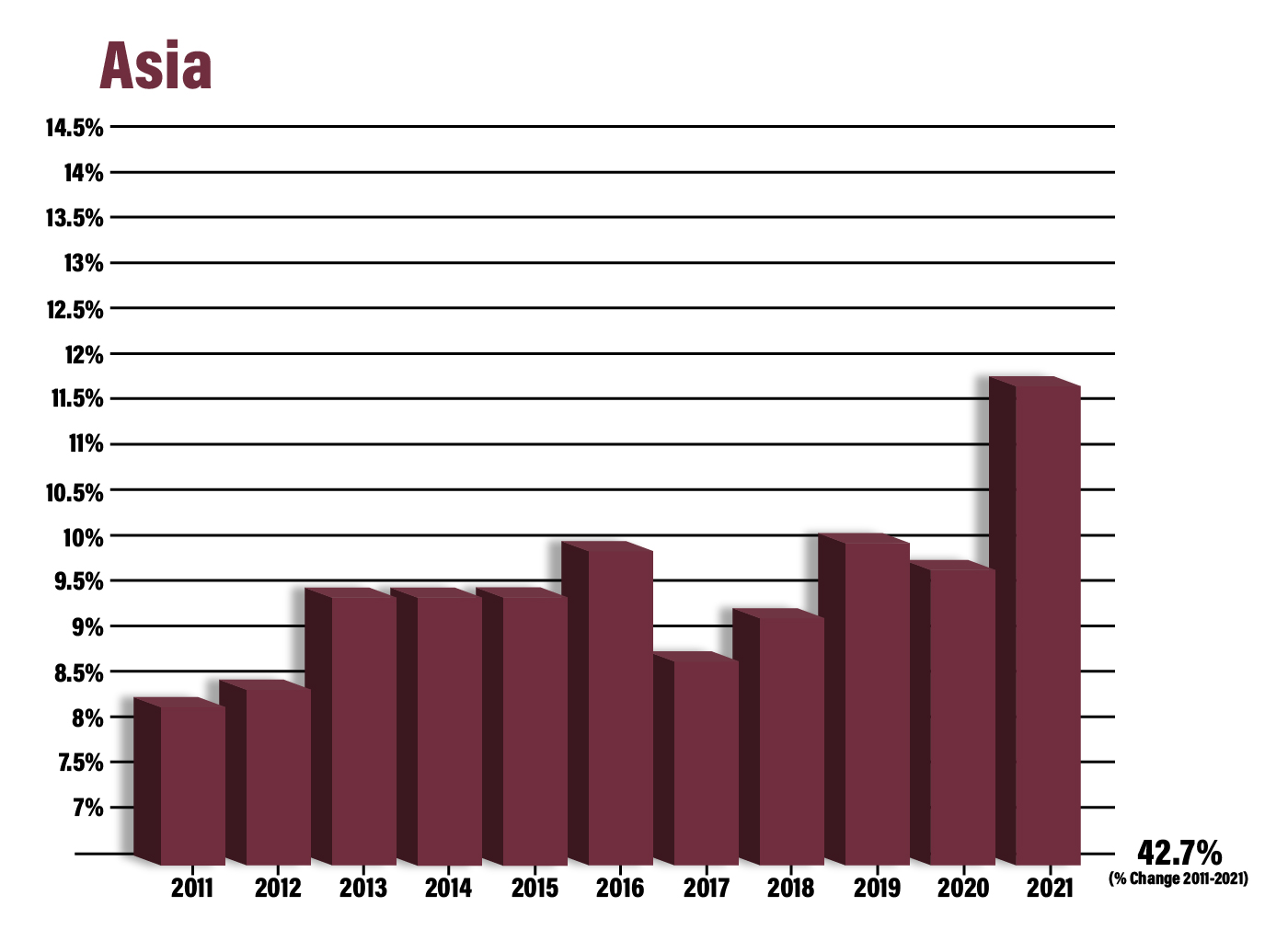

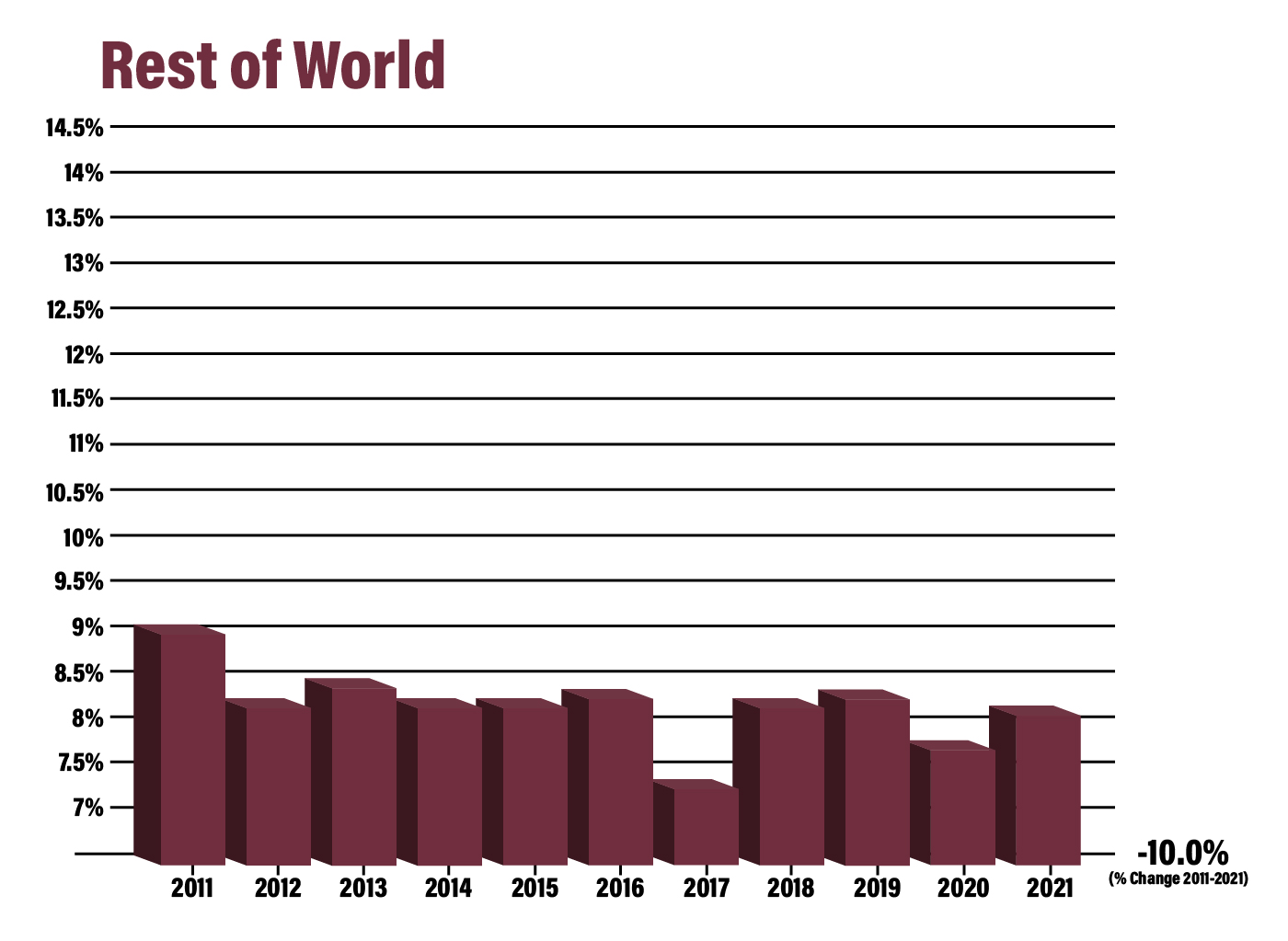

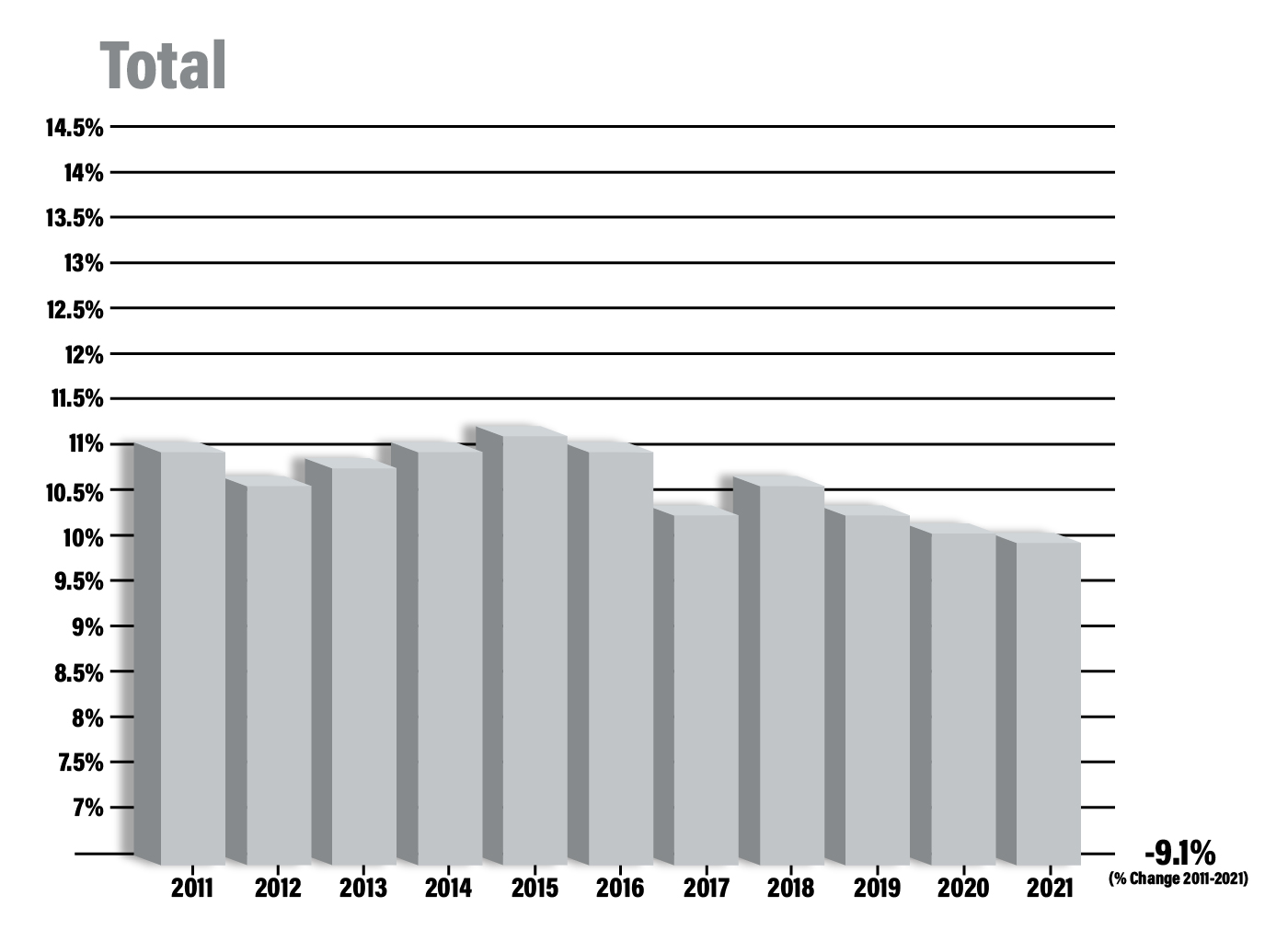

One way of watching trends in family business worldwide is to study stock indices. Below, we look at family firms in 37 countries around the world. As you can see, their prevalence has declined recently in the U.S. and Canada but increased in Mexico. Similarly, family firms are growing in Asia but less so in Europe and other parts of the developed world. In advanced economies, family owners are gradually selling their shares to nonfamily individuals and institutional investors. In emerging economies, maintaining family ownership and control is advantageous because it substitutes for the legal systems and property rights protections found in advanced economies, preventing the appropriation of wealth by outside parties. Nevertheless, family ownership and control among smaller firms remains ubiquitous around the world because it provides stakeholders with the lowest costs while exercising the greatest control.

Source: NRG International

INFORMATION – Firm Success

How Do Family Firms Maintain Superior Performance?

by Dr. Jim Chrisman

Besides the specifics of their strategies and resources, family firms have several advantages over nonfamily firms. Those include:

- Stronger relationships among owners and managers because they have common purpose

- Conservative investment practices because they’re investing their own money

- Greater decision-making discretion because it’s their company

- Greater difficulty raising outside capital because they don’t want to give up control

- Managerial capacity limits because they want to keep decisions in the family

- Reluctance to take risks because their family wealth is less diversified

The impact of these factors on performance depends on the strength of the firms’ advantages and the seriousness of their disadvantages, how the advantages and disadvantages are used and the extent to which the competitive environment rewards the strengths and punishes the weaknesses.

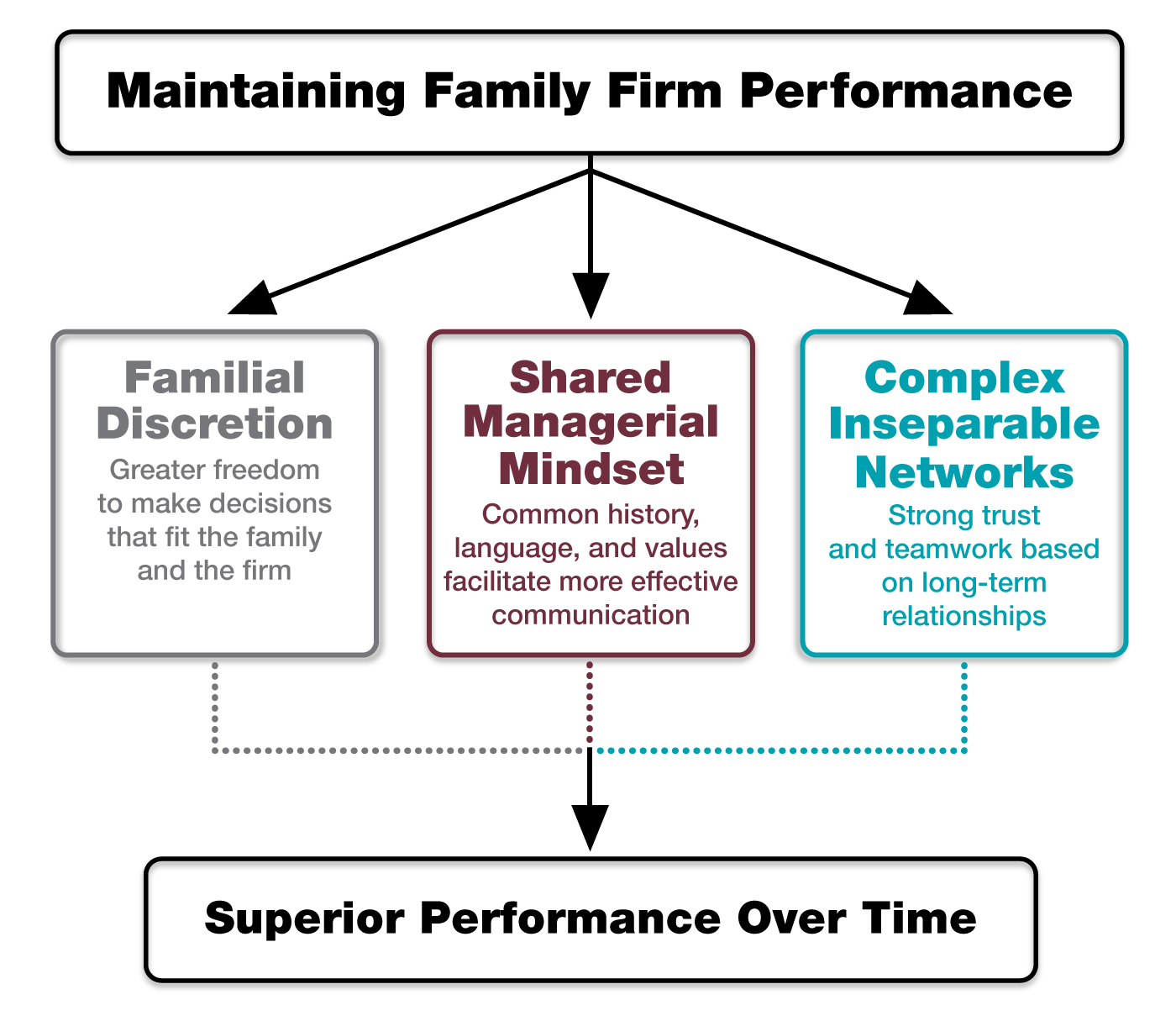

Until now, no one has studied whether family firms are better able to maintain superior performance once it’s been achieved. Because maintaining superior performance is important for family owners who want to pass on the firm to the next generation, we addressed this research question as one that gets to the heart of what family firms are all about. Based on the idea that the characteristics of family firms make them more persistent and reliable, we expected they would be better at maintaining excellence, and the results of our study showed we were right.

In general, successful family firms have a few “isolating mechanisms” that prevent competitors from duplicating their strategies and critical resources. First, because they have greater discretion to make decisions that best fit the nature of the family and the firm, the ability of competitors to duplicate these strategies and resources is limited. Second, when they generate or obtain resources that create value, they’re more likely to build upon them over time because the owner-manager group is more closely knit and better able to communicate. Thus, family firms are able to maintain superior performance by building consistently and persistently on the historic decisions of their founders.

The funny thing is those tight relationships between family members are not easy to figure out. Their shared history, language and identity create a common managerial mindset that enables them to more easily recognize, assimilate and utilize each other’s knowledge. This makes communication easier and more effective, but complex for outsiders to understand. Even family owners and managers themselves don’t fully understand it. Fortunately, family firms tend to be somewhat conservative and unlike Coke, Budweiser, or Jaguar, less likely to fool around with something that’s working.

The complex networks that family firms build over time have the additional characteristic of inseparability. They gain advantages from sticking together and building on the trust and teamwork that has developed. This is self-reinforcing because the skills of individual family members tend to be more valuable within the family context than somewhere else. The inseparability of family members enhances their willingness to keep the human, social and other productive assets of the firm intact and to plan for their expansion and replacement by the next generation. This is an obvious but powerful advantage because resources that are jointly held by family members are unlikely to be easily imitated or appropriated by other firms.

In conclusion, there’s no universal magic formula for family firm success. However, family firms that learn and build on their history can create social relationships among their members that are not easy to tear apart. They’re more likely to develop their own unique formulas that will lead to superior performance for a very long time.

Adapted from: Fang, H., Kotlar, J., & Chrisman, J.J. (forthcoming). Family control and sustainable competitive advantage.Family Business Review, and, Fang, H., Chrisman, J.J., & Holt, D.T. (2021). Strategic persistence in family business.Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 45, 931-950.

FAMILY ENTERPRISE SPOTLIGHT

Rooted in Mississippi, Reaching the World

The Taylor Family Business Story

by Dr. Laura Marler

Founded in 1927 as Taylor’s Garage and Machine Shop, the Taylor Group of Companies (Taylor) is now composed of 16 different enterprises and more than 1,700 employees worldwide.

Foundational family values and an unending commitment to meeting the needs of markets in innovative ways have carried Taylor into its third generation of business. Headquartered in Louisville, MS, the company is now welcoming the fourth generation of family into the fold and nearing the celebration of its 100th anniversary.

After a conversation with CEO Lex Taylor, you realize that family and non-family alike are valued and involved in decision making. As the company has grown, it’s been reliant on identifying qualified talent and is particularly adept at hiring individuals who thrive in its community. A glance at the company newsletter, Taylor Today, reveals a page recognizing years of service – 35, 40, 45, and 50 years. This single page of recognition speaks volumes and tells the story of longevity, continued success, and the value of employees.

Lex, whose first job at age 15 was sweeping out the receiving bay and keeping the dock clean at Taylor Machine Works, believes that his grandfather’s guiding values – faith, vision, and work – still drive the family business today. When asked about how a family business can succeed across generations, he emphasizes the roles of vision, finance, diversification, and relationships in company growth. Even during successful times, Lex advises, a business, especially manufacturing, should vigilantly be considering “the next big idea.”

Lex also advises that as a global company “you must have senior people you can have confidence in” when operating across the international landscape.

The Taylor family’s ability to navigate the complexities across generations has been clear. Planning for future generations goes hand in hand with the pursuit of continued success through growth.

The family is committed to succession planning to leave the next generation well-positioned. Lex’s pride in the fourth generation is evident when he expresses the passion they already demonstrate, and he is more than willing to give them opportunities to learn. He believes that success in getting that generation incorporated lies in providing “good opportunities to let them walk in different parts of the company” just as he did growing up and into his career.

Lex Taylor (2nd from right) along with sister Teresa Taylor Ktsanes and brother Robert Taylor are surrounded by the younger generation of their family who are involved in the business.

Mississippi SBDC

America’s SBDC

Mississippi State University is an equal opportunity institution.

Editor: Dr. Laura Marler

Head, Department of Management & Information Systems & Jim and Pat Coggin Endowed Professor of Management